Part 3, Chun Tae-il’s Actions

Injustice witnessed in a sewing factory

In 1967, Chun Tae-il became a tailor, but he felt powerless to help the vulnerable young women workers on his own. The fundamental issues of poor working conditions, long mandatory hours, and low wages stemmed from complex social problems.

During the summer of 1967, Chun learned about the “Labor Standards Act” from his father and dedicated himself to studying it. He discovered that Article 42 of the Labor Standards Act stated, “Working hours shall not exceed 8 hours per day and 48 hours per week, excluding break time.” Additionally, Article 45 required that “the employer shall give the workers at least one paid holiday per week on average.” Moreover, the law prohibited night shifts for workers under the age of 18. Despite these regulations, they were largely ignored at Pyeonghwa Market, and shop owners faced no penalties.

During the summer of 1967, Chun learned about the “Labor Standards Act” from his father and dedicated himself to studying it. He discovered that Article 42 of the Labor Standards Act stated, “Working hours shall not exceed 8 hours per day and 48 hours per week, excluding break time.” Additionally, Article 45 required that “the employer shall give the workers at least one paid holiday per week on average.” Moreover, the law prohibited night shifts for workers under the age of 18. Despite these regulations, they were largely ignored at Pyeonghwa Market, and shop owners faced no penalties.

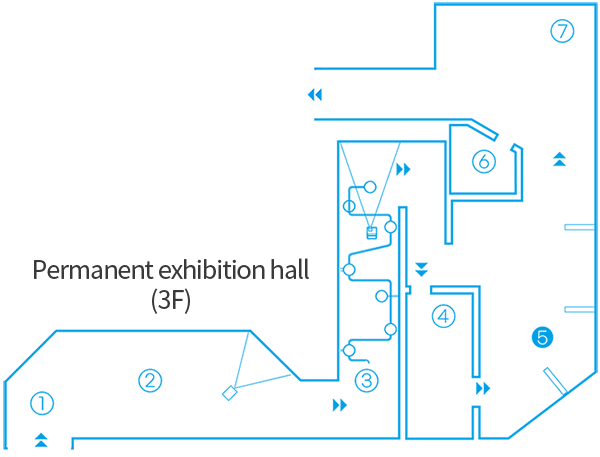

Diary of Chun Tae-il

This is a replica of Chun Tae-il's diary, which he maintained for 22 years during his brief life. In the diary, he expresses his concerns about the harsh realities and uncertain future, along with reflections on the dreadful working conditions at the Pyeonghwa Market sewing factory, and his plans to establish a model company.

The beginning of the labor movement

In 1969, Tae-il founded the Babo-hoe, an organization of tailors that started with just ten members. As the chairman of the Babo-hoe, he created a questionnaire to assess the actual working conditions in the garment sweatshops of Pyeonghwa Market.

After gathering the survey results, he analyzed the findings and submitted a petition to Seoul City Hall and the government labor office. Unfortunately, the Babo-hoe's efforts were short-lived due to a lack of funding and insufficient results. Nevertheless, Chun Tae-il remained determined and wrote a letter to President Park Chung-hee detailing the harsh realities of Pyeonghwa Market.

In 1970, he founded Samdong-hoe, an association of garment cutters. A fact-finding investigation was reinitiated, and the struggle continued with petitions submitted to Dongyang Broadcasting, Seoul City Hall, and the Labor Administration Office. For the first time, his research on the harsh working conditions was reported in the social section of the Kyunghyang Shinmun under the headline, “Working 16 Hours a Day in Small Rooms.”

After gathering the survey results, he analyzed the findings and submitted a petition to Seoul City Hall and the government labor office. Unfortunately, the Babo-hoe's efforts were short-lived due to a lack of funding and insufficient results. Nevertheless, Chun Tae-il remained determined and wrote a letter to President Park Chung-hee detailing the harsh realities of Pyeonghwa Market.

In 1970, he founded Samdong-hoe, an association of garment cutters. A fact-finding investigation was reinitiated, and the struggle continued with petitions submitted to Dongyang Broadcasting, Seoul City Hall, and the Labor Administration Office. For the first time, his research on the harsh working conditions was reported in the social section of the Kyunghyang Shinmun under the headline, “Working 16 Hours a Day in Small Rooms.”

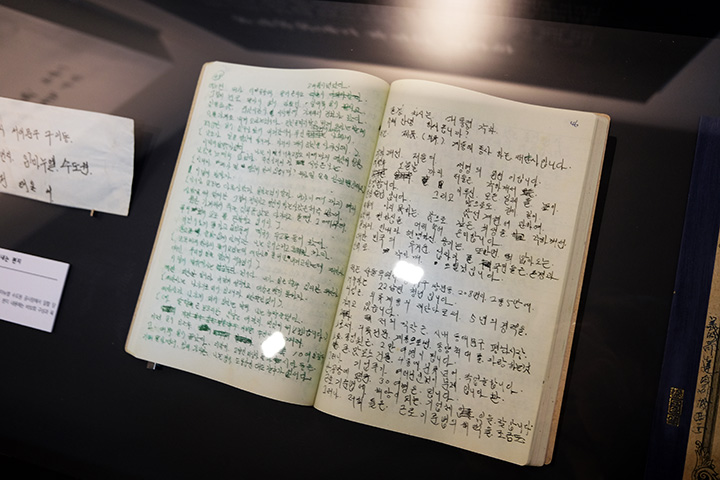

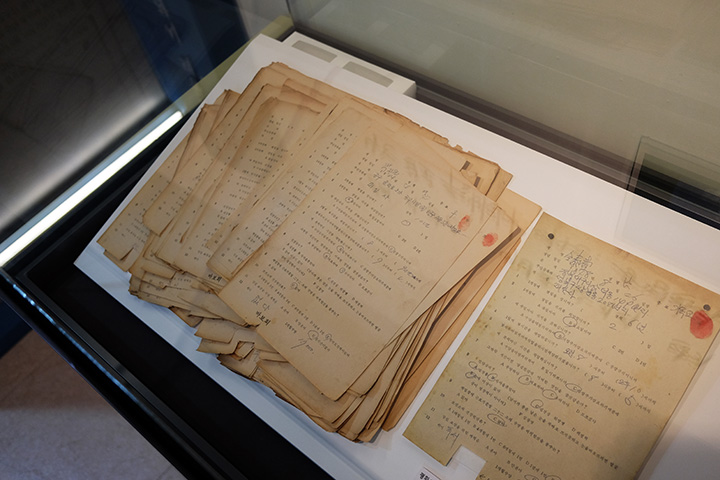

Pyeonghwa Market Labor Conditions Survey

Babo-Hoe created a questionnaire to investigate the working conditions of employees at Pyeonghwa Market. The workers were asked to provide information about their working hours, occupational illnesses, holiday work, and wages. Based on the survey results, complaints were submitted to the Ministry of Labor and the media.

Chun Tae-il's decision

He persistently organized meetings and protests against officials from the Labor Administration Office for some time.

However, the government’s annual inspection concluded without any discussion on improving working conditions, which only deepened his feelings of betrayal and frustration. In response, he prepared for a demonstration, planning to burn copies of the Labor Standards Act.

When the police stopped him from burning the copies of the Labor Standards Act, he set himself on fire, chanting "Obey the Labor Standards Act!" and "We are not machines!" He wanted to improve his colleagues' working environment through his death.

When the police stopped him from burning the copies of the Labor Standards Act, he set himself on fire, chanting "Obey the Labor Standards Act!" and "We are not machines!" He wanted to improve his colleagues' working environment through his death.

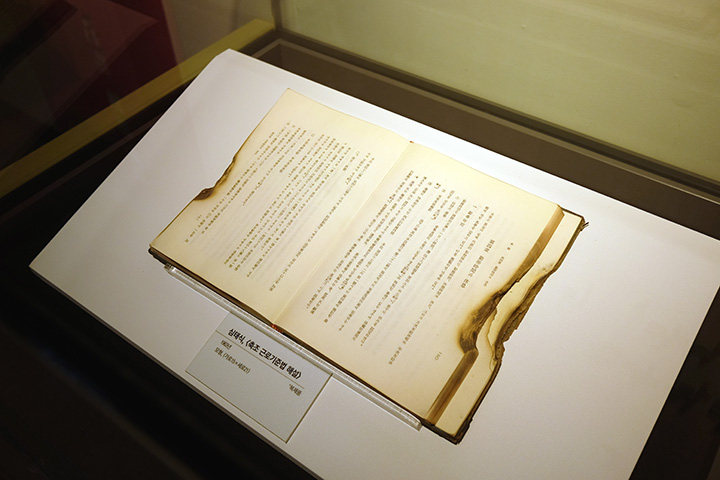

Explanation of the Labor Standards Act Written by Shim Tae-sik, Replica

Tae-il learned about the Labor Standards Act from his father and always carried a book on it to study. It is said that even during his self-immolation protest, he was holding a book on the Labor Standards Act in his hands. This particular book was published in 1963 and closely resembles the one Tae-il owned. The replica of the burnt book on display allows visitors to feel the emotions of Chun Tae-il, who must have been frustrated and distressed after realizing that the Labor Standards Act, which had once seemed like a ray of hope, was ultimately ineffective.