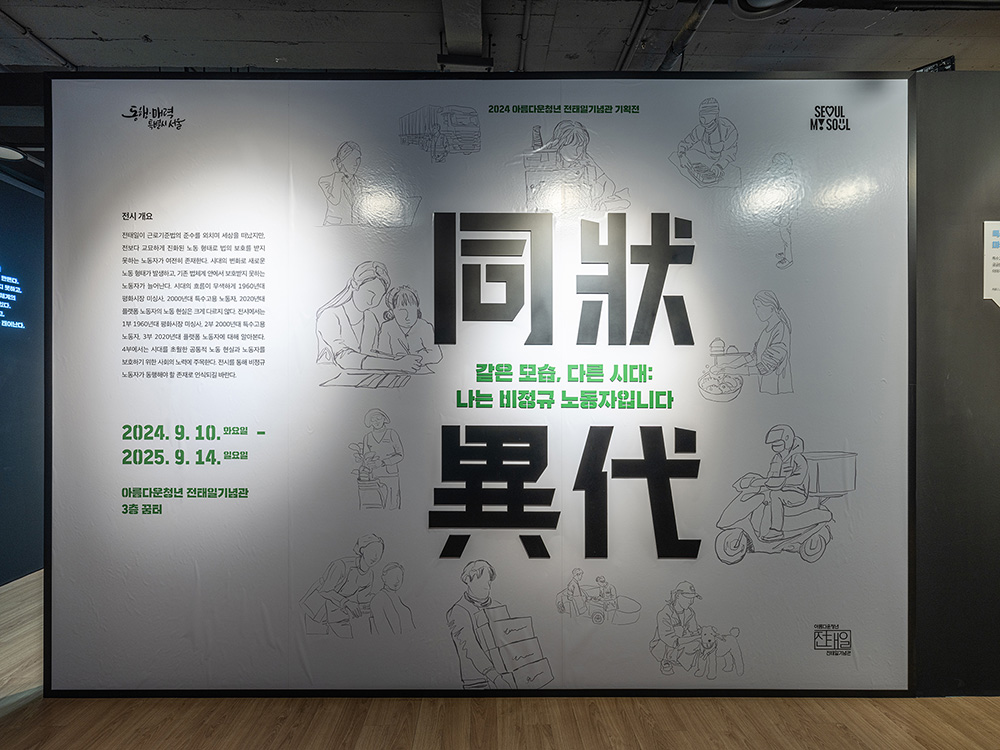

Same Appearance, Different Era: I Am a Non-Permanent Worker

2024.09.10 ~ 2025.09.14

Preface

Although Chun Tae-il gave his life while demanding compliance with the Labor Standards Act, Korea still has workers not protected by the law as the job market has evolved into more sophisticated forms that exploit loopholes in existing regulations.As times change, new types of work emerge, and the number of staff left unprotected by the legal systems increase.

Despite the passage of time, the labor reality of sewing workers at Pyounghwa Market in the 1960s, special contracted staff in the 2000s, and platform workers in the 2020s is little different.

This exhibition explores all three types of workers in their respective eras.

The final section highlights the common labor realities across these times and society’s efforts to protect workers.

The hope is that this exhibition can boost recognition of non-permanent staff as companions in society’s journey.

prologue

The flow of time creates new forms of labor.The law has failed to keep up,

often leaving workers out of the social protection system.

Changes worldwide lead to job diversifaction.

1. 1960s : Sewing Workers

1-1. Birth of the Industrial Workforce

1962 saw the effectuation of the first Five-Year Economic Development Plan, after which Korea achieved annual economic growth of over 8 percent from 1963 to 1979.The government-led, export-driven industrialization of the 1960s was fueled by low wages and long working hours. Garment manufacturing grew rapidly from the late 1960s and flourished during the 1970s and 1980s, driven by cheap labor of young women from the provinces. Despite their efforts, sewing workers faced unstable employment and income.

Sewing Factories at Pyounghwa Market

In the 1960s, sewing factories began to proliferate around Cheonggyecheon Stream in Seoul. Pyounghwa Market was opened in 1961, followed by Dongsin Market in 1962, Tong-il Shopping Mall in 1968, and Donghwa Market in 1969. Despite thriving due to the expanding domestic market and surging exports in the 1970s, sewing factories at Pyounghwa suffered from poor conditions as over 90 percent of the workplaces there were two-story attics designed to maximize productivity. On average, workers labored for 15 hours a day with their backs bent and breathed in fablic dust at attics only about 1.5 meters high.

Employment Conditions of Sewing Workers at Pyounghwa Market

In the 1960s and 1970s, many sewing staff at Pyounghwa Market were paid by piece, producing garments using sewing machines, fabrics, and accessories provided by the company. Part of their pay went to one to three apprentices.

Their high workload led them to take stimulants and skip bathroom breaks. They occasionally did not work due to lack of orders, leading to unstable wages and employment. Despite the Labor Standards Act enacted in 1953, such workers were not protected by law.

1-2. Permanent Status

In Korea, permanent employment typically means a worker being directly hired by a company with the expectation of lifelong employment, working under the employer’s supervision at their business site. According to Article 50 of the Labor Standards Act, employees should work 8 hours a day, 40 hours a week. Each company must follow rules on hiring, duties, and working conditions and workers are entitled to job stability, a living wage, training, and welfare benefits. An employee keeps their job except in the case of resignation or dismissal. Since the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis, however, restructuring and government policy have fueled a major rise in non-permanent workers.2. 2000s : Special Contract Workers

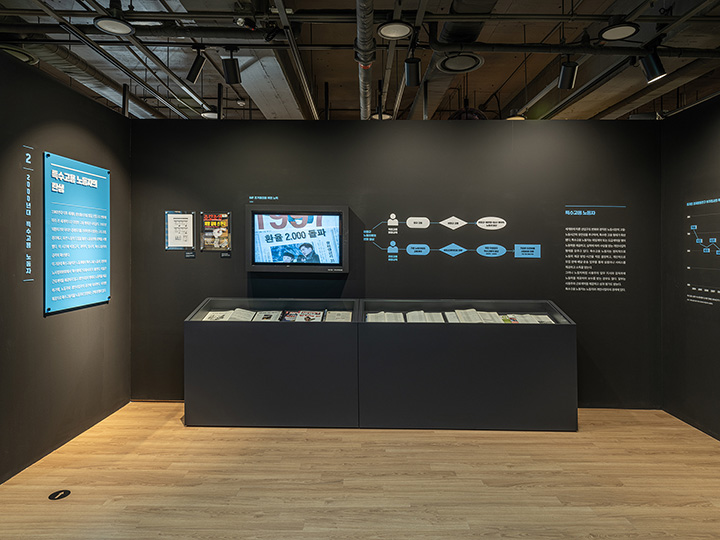

2-1. Rise of Special Contract Workers

Since the 1980s, globalization, advances in information and communications technology, and shifts in the industrial structure have led to more forms of employment worldwide. During the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis and the subsequent economic downturn, the Korean government pursued policy that allowed restructuring, layoffs, and staff dispatch to increase labor flexibility. This led to a rapid increase in non-permanent, fixed-term, temporary, and special contract workers. Labor organizations call these workers “special contract workers,” while the government and the Economic, Social & Labor Council (a tripartite presidential advisory council of government, labor, and management) dub them “employees in special type of employment.” Such laborers are considered individual business entities rather than signatories to traditional labor contracts, positioning them between permanent employees and independent business operators. This status has fueled debate over recognizing them as workers.Special Contract Workers

As globalization reshaped industrial structures and the labor market grew more rigid, the need for worker and employment flexibility led to the rise of special employment classifications. Special contract workers operate under commission or subcontract agreements to provide labor and receive performance-based pay, effectively functioning asthe self-employed. They generally determine their own work methods and hours, engaging in activities like recruiting, sales, delivery, and transportation. Many, however, are under direct employer supervision and receive instructions and pay much like permanent staff, with some even formally assessed under employment contracts. Thus special contract workers remain in a gray area between traditional employees and independent contractors.

Occupations for Special Contract Workers

Special contract workers are commonly found in easily outsourced occupations. For example, container truck drivers initially employed by companies purchased their own trucks to become independent contractors, receiving fees instead of wages through new contracts. Common jobs for such workers include construction equipment operators, couriers (delivery drivers), insurance agents, door-to-door salespeople, home-study teachers, golf caddies, TV writers, and paid designated drivers (daeri-unjeon).

3. 2020s : Platform Workers

3-1. Birth of Platform Workers

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, marked by digital transformation and rapid advances in artificial intelligence, has led to the rise of online platforms in global industrial restructuring. The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 further expanded platform industries as remote and contactless living became the norm. The European Union predicts that the number of platform workers will jump over 50 percent by 2025 from 2022. The platform industry has grown from manual labor such as delivery driver and quick delivery services, designated drivers (daeri unjeon), and cleaning to freelance and professional sectors like design, high-tech programming, translation, tax accounting, and legal services. Platforms offer consumers convenience and satisfaction while giving workers income opportunities not bound by specific times or locations.Platform Workers

Platform workers offer labor and services through online platforms. Their work is evaluated by consumer reviews and ratings, and those with poor reviews are at risk of not getting job assignments. In 2019, 36.5 percent of such laborers earned under KRW 1 million per month, a generally low-income level. Frequent changes in fee structures also make it difficult for platform workers to predict their earnings. On average, they work 8.22 hours per day, with many working six days a week. Designated drivers, quick-delivery couriers, and truck drivers often face extended working hours ranging from 9 to 13 hours per day. Thus laborers in this industry face irregular working hours, unstable income, and job insecurity.

Delivery Drivers

Platform delivery workers use their own vehicles to deliver items and get paid per delivery. Most are men who work long hours. Although they have the freedom to choose their work and schedule, the platform determines pay rates and assignments, making both the job and income unstable. Platforms manage delivery workers by limiting assignments or suspending accounts based on performance reviews, including customer ratings. Additionally, expenses like those incurred by waiting time and fuel costs are not reimbursed, something that further impacts their earnings.

Domestic Workers

These workers, mostly women, provide cleaning and laundry services through apps. Their hourly wages are generally below the minimum wage. For example, their average pay in 2022 was KRW 8,700 per hour, lower than the minimum wage of KRW 9,160. Expenses such as fuel, travel time, and cleaning supplies are not covered, which drive down their earnings. Their performance is also evaluated through customer ratings and reviews.

Information & Communication Technology Developers

Web-based freelance platform ICT developers either complete outsourced projects under subcontracts or work on-site or remotely for clients under short-term contracts. The latter agreements involve working as permanent employees typically for three to four months but sometimes as short as one day to as long as over a year. Most ICT developers are men, work about 40 hours a week, and generally have relatively high monthly earnings.

Pet Sitters

These animal lovers walk and care for pets and get their gigs through apps, with most being in their 20s and 30s. To ensure quality care, sitters must verify their identities, demonstrate relevant skills, and complete specialized training. Recently, platforms exclusively for veterinarians and veterinary students and technicians have emerged. Expenses like fuel, toys, and treats are not included in their incomes, and customer ratings and reviews play a major role in determining their assignments.

4. Reason for Hope

4-1 Non-Permanent Employment

New jobs have emerged in line with shifts in global trends. Non-permanent as opposed to permanent employment includes a variety of occupations with diverse structures, making it challenging to define non-permanent work as a single concept. Sewing workers in the 1960s, special contract workers in the 2000s, and platform staff in the 2020s all suffer from the traits of unstable employment and income. These gigs often fall through the gaps of the legal framework. Special contract and platform workers, despite having the traits of traditional workers, get classified as individual contractors and are thus particularly vulnerable. They are not protected by the Labor Standards Act or the Social Insurance Act and face restrictions in exercising fundamental labor rights.Gray Area Between Workers and Individual Business Entities

To widen legal protection for new jobs, work and pay conditions must be recognized as similar to those of wage workers. Recognizing special contract and platform workers as “employees” remains a contentious issue, however. While they often provide labor under the direction and control of employers or platforms in return for fees, many are legally considered “individual business entities.” This classification denies them access to labor protection like the minimum wage, social insurance, employment security, and retirement benefits.

4-2. Companionship

Today, the world seeks to protect non-permanent laborers. In Korea, the government is expanding social insurance coverage of select special contract and platform workers in industrial accident compensation and employment insurance. The use of standard contracts is also being encouraged to promote equity in business relationships. Social organizations and labor unions are striving to ensure legal and institutional protections. Worldwide, laws also seek to protect workers in newly emerging fields in response to changing trends. Society is thus moving toward coexisting with the growingly diverse forms of workers.Expansion of Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act for Special Contract & Platform Workers

Insurance for industrial accident compensation is being expanded to include special contract and platform workers. In July 2023, an amendment to the Industrial Accident Compensation Insurance Act took effect to cover “labor providers” like these staff.

Employment Insurance Coverage of Special Contract & Platform Workers

Special contract, platform, and freelance workers often have low and irregular incomes, but they previously had to pay the full premium for employment insurance as “individually insured persons.” With expanded coverage of mandatory employment insurance, they now qualify for benefits given to permanent staff such as unemployment allowance and maternity benefits , in cases of involuntary loss of job.

Recognition of Worker Status under Trade Union Act

Due to the variety of jobs that special contract workers perform, those in select occupations are recognized as “workers” under the Trade Union and Labor Relations Adjustment Act. They include golf caddies, home-study teachers, TV actors, car dealers, rail station canteen owners, couriers, and designated drivers. Yet other jobs such as insurance agents and ready-mix concrete transporters do not qualify.